Blog

Tags:

REACH Lab Blog Entry #1 - Blanca Velazquez-Martin & REACH Project Investigators

Blanca Velazquez-Martin & REACH Project Investigators

Music and the arts cannot erase poverty, but…what if we had scientific evidence of the potential for the arts to counter some of the toxic effects of adversity on young children?

With this question in mind, we welcome you to the Research on Education and the Arts in Childhood (REACH) blog. Through this space, we will present a series of posts highlighting work from our research team that builds an evidence base for how high-quality creative arts experiences can mitigate the effects of poverty and related forms of adversity, and promote the flourishing of young children.

Across centuries, humans have drawn upon creativity, imagination, invention, and artistic skill as sources of resilience, healing, connection, and learning. At the Research on Education and Arts in Childhood (REACH) Lab, with support from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA), we partner with community organizations that promote early childhood arts education and creative experiences to study their impact on children and families facing economic hardship. We take a strength-based approach to examine what could happen, for social-emotional health and wellbeing, if children and families were provided with high-quality, sustained opportunities for experiencing, engaging, imagining, inventing, and originating. We have begun our inquiry into this question with an in-depth set of studies focused on music.

Our keystone study focuses on Settlement Music School’s Kaleidoscope Preschool Arts Enrichment Program. In a prior NEA-funded study focused on this preschool, we asked, “Can the arts get under the skin?” and the answer was Yes. Music and other arts classes related to reduce levels of the stress hormone cortisol for children facing poverty and related adversity. In the keystone study, the REACH team will work to identify the types of music experiences that might be linked to these ameliorative effects, as well as investigate the impact of music and correlated physiological changes on other aspects of child self-regulation.

Another REACH study focuses on Carnegie Hall’s Lullaby Project, implemented in Philadelphia in partnership with World Café Live. This project pairs new parents and caregivers with professional artists to write and sing personal lullabies for their babies and toddlers. Existing data suggests an important impact on the parent-child relationship, and the present study aims to better understand how such shared music and creative activities might increase mutual regulation and attachment as well as nurture early communicative development in young children and their caregivers.

The final REACH study in this set focuses on Play on Philly, an intensive orchestral music education program for elementary school students. Our prior studies have linked this programming to increased child self-regulation and persistence, and the present study aims to better understand the physiological mechanisms underlying these effects.

Led by an interdisciplinary team of investigators that includes Drs. Ellie Brown, Dennie Palmer Wolf, and Steven Holochwost, the establishment of the Research on Equity via the Arts in Childhood (REACH) lab has been made possible by a cooperative award from the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) through their Arts Research Labs program (https://www.arts.gov/initiatives/nea-research-labs).

Drs. Brown, Wolf, and Holochwost bring diverse expertise to this project. Brown is a licensed clinical psychologist and Professor of Psychology at West Chester University, Wolf is WolfBrown’s principal researcher and one of the nation’s leading arts education researchers and evaluators, and Holochwost is a developmental neuroscientist serving as an Associate Professor at CUNY’s Lehman College and Director of Research for Youth & Families at WolfBrown. All three investigators are dedicated to using developmental science to address social inequities and improve the lives of children placed at risk by poverty and other forms of adversity. They join with their community partners and with a vibrant team of graduate, postgraduate, and undergraduate scholars to pursue the present ambitious arts research agenda.

The REACH agenda will help investigators and research-trainees take a deeper dive into the ways music and the arts can directly benefit child and family wellbeing. Through this blog, we hope to share more about our research questions, plans, and findings, and to engage your mind in thinking with us about the possibilities for using creativity and the arts to advance shared goals of equity. We also hope to share more about the wonderful children, families, and community partners engaged in the music and arts activities that are central to this project.

Join us as we learn more about the impact of music and arts programming on young children and families, and REACH with us to consider how music and the arts might be implemented to provide impactful arts experiences, alleviate stress, and promote positive development for children facing adversity.

“Music and the arts cannot erase poverty, but they may have the potential to counter some of the toxic effects of adversity on young children.”

~ REACH Lab Investigators

REACH Lab Blog Entry #2 - Dennie Palmer Wolf and Kathleen Hill

The REACH Lab is excited to announce that several researchers' work on orchestral music as a context for fostering growth mindsets was selected for inclusion in a recently published volume from Frontiers in Psychology titled "The Psychological and Physiological Benefits of the Arts." We are honored to be included in the growing global conversation about the arts as a human experience with major potential to encourage, heal, and connect. The volume is especially useful as it contains research rooted in a full range of artistic fields: dance, music, theater, and visual arts, and includes findings with participants at every stage of human development: childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and seniors. Finally, the volume places US-based work in conversation with researchers from around the globe, helping to initiate a much more international exchange of perspectives and methods.

For us, as developmental researchers, we are especially excited to be contributing arguments for and evidence of the arts as a strategy for equalizing children’s access to opportunities for growth fueled by the arts. In particular, we are committed to the examination of the impact of arts participation on social-emotional outcomes like self-regulation, growth mindset, and empathy. To our way of thinking, arts experiences – when thoughtfully and well delivered – nurture these capacities. Practicing an instrumental part requires the kinds of candid self- assessment and investment in change that may promote growth mindset. Improvising dialogue from a character’s point of view may stretch the understandings that build empathy. In this sense, such investigations into the overlap between the arts and social-emotional learning dissolve the dichotomy between instrumental and intrinsic approaches to evaluating artistic outcomes.

Our contribution to the volume, “Planting the Seeds: Orchestral Music as a Context for Fostering Growth Mindsets” explores these kinds of outcomes. It brings together the work of REACH Lab members Steven J. Holochwost, Eleanor D. Brown, and Dennie Palmer Wolf, with insights from Kate E. Anderson, Judith Hill Bose, and Elizabeth Stuk. It was because of the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) research initiatives that WolfBrown and West Chester University scholars joined together to author this contribution, and we are grateful to our colleagues at the NEA for their leadership and support.

We also are thankful to our partners at the Longy School of Music of Bard College as well as the programmatic partners for their scholarship and collaboration. Additionally, we would like to thank the Mellon Foundation and the Buck Family Foundation for supporting this vital work.

The Frontiers e-book, comprising nearly 90 articles selected from an international set of researchers is now available online on the publisher’s website.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #3 - Dr. Ellie Brown with Drs. Dennie Palmer Wolf and Steven Holochwost

Guide or Get Out

To optimize music’s benefits for young children, should teachers guide or get out of the way?

Here in the REACH Lab, we’ve been probing the role of teachers in arts education. Our past work has indicated that certain music experiences relate to decreased levels of the stress hormone cortisol for young children, potentially alleviating the toll imposed by poverty stress. In a recent REACH project, we’ve dug into this finding and examined whether the benefits of music change depending on: (1) whether teachers versus children direct the music activities; and (2) the quality of teacher-child interactions around these activities.

Research can be fun when you find evidence of something you already know is true. And we all know high quality teacher-child interactions matter, so we expected to see this in the data - and we did. For children in an arts-integrated preschool, music activities that were characterized by higher quality teacher-child interactions were associated with decreased levels of child cortisol compared with music activities that had less teacher-child interaction or less supportive interaction - an affirming finding.

But for many of us, it’s most exciting when you explore questions for which we don’t yet know the answer, and that was the case with the question about teacher or child direction. We were fascinated to see what the data would show about whether music had the greatest benefits for child stress regulation when teachers directed the activities or whether it was most beneficial when children did.

On one hand, there is evidence that adult involvement in creative and other play activities promotes the benefits of those activities for young children’s development (cf., Fisher et al., 2013). However, there is also some evidence suggesting that the benefits of arts education for children’s HPA-axis activity is explained, in part, by the extent to which those activities offer children an opportunity for child-directed or free play. For example, the arts activities that were associated with lower levels of cortisol in a study conducted by Toyoshima and colleagues (2011) were all self-directed.

For our study at the arts-integrated preschool, the data suggested lower stress levels when children directed the specific music activities. This was particularly interesting given that this finding was apparent alongside that for teacher-child interaction: In the final model, child stress levels were lowest when children directed the activities and teachers provided high quality support around these activities. How fascinating that a combination of child autonomy and teacher support was most powerful!

I’ve reflected on these findings several times when watching children during visits to the preschool. Recently, I watched Jayden, a child who struggles to regulate his behavior, as he engaged in a music class in which children had opportunities to play tom-tom drums. During the first part of the class, which was teacher-directed, he showed easy skill with the instrument, coordinating hands and beats to the teacher’s instructions. I could imagine that if he received continued instruction and support for his skill development, music generally, or percussion, specifically, could become an area of competence and pride for him - perhaps supporting more general resilience. Given these potential benefits, as a clinical psychologist, I certainly wouldn’t suggest we remove teacher direction from an early childhood music program - even if we only were concerned with social-emotional outcomes.

But as I was observing through the lens of our REACH findings (and not trying to counter confirmatory bias that may have been operating), it did seem to me that Jayden was in a state of considerable arousal as he was following the teacher direction. Some of this most likely was adaptive, as he was attending and following instructions - or at least mostly following them. But his occasional vocalizations out of turn and his inability to stop beating the drum when asked suggested he was not fully regulated…yet.

Jayden’s body showed visible relaxation as the class transitioned to a child-directed segment, where children had an opportunity to experiment with different instruments. The music teacher and an assistant who also was present rotated and supported children around their chosen activities. Jayden stuck with the tom-tom drum, yet was now moving to his own rhythm, without tension. I couldn’t help but think levels of the stress hormone cortisol now would be lower than during the teacher-directed part.

Given the lens of our study, I was curious to see how Jayden would behave as the teacher concluded the class with a group goodbye song and dance. This song was familiar to the children, so it may be unwise to compare it to the first group drumming activity. Nonetheless, I wondered if Jayden would struggle to contain his energy, perhaps vocalizing out of turn again or continuing motions beyond their turn. Interestingly, he did not. Had the child-directed portion helped him to regulate in a way that now supported his more relaxed participation in the cooperative goodbye song? We don’t yet have a study that provides data on this, but it certainly seems possible, and would be interesting to explore.

Should teachers guide or get out of the way? Undoubtedly, there are times for each of these pedagogical strategies. But our recent REACH study suggests that if goals of child stress reduction are the priority, then teachers should neither guide nor get out of the way - rather, they might facilitate music experiences that allow for children to direct activities while receiving high quality teacher support.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #4 - Highlights from REACH Convening - Ellie Brown with WCU Photographer Erica Thompson

Highlights from REACH Convening - Ellie Brown with WCU Photographer Erica Thompson

Thanks to WCU Photographer Erica Thompson for capturing highlights from the REACH Convening!

Jan Michener, Director of Arts Holding Hands and Hearts (AHHAH), talks with WCU Psychology BS students Rochell Blignaut, Anna Carroll, and Jadyn Branch about their research poster on classroom chaos and child cortisol levels.

From left to right: Noah Aldabishi, Melissa Ceren, and Steven Holochwost (CUNY's Lehman College) stand with Blanca Velazquez-Martin (WCU Psychology Master's Program Alum), Tarrell Davis (Executive Director of Early Childhood at Settlement Music School), Shanelle Stovall (WCU PsyD Student), Ellie Brown (WCU Professor of Psychology), Estefania Ortiz (WCU Psychology BS Alum), Amanda Bryans (Federal Office of Head Start Education and Research to Practice Supervisor), and Sunil Iyengar (National Endowment for the Arts Director of Research and Analysis)

Jimena Violente, Musician and Lullaby Teaching Artist, presents to REACH attendees

As can be seen from the purple and gold posters, WCU students presented a range of scholarly projects.

A REACH attendee snapped this photo of lead investigators Dennie Palmer Wolf, Ellie Brown, and Steven Holochwost at the end of a successful day!

REACH Lab Blog Entry #5 - Dennie Palmer Wolf’s Repost of Rita Giordano

Dennie Palmer Wolf’s Repost of Rita Giordano

This post highlights an article by reporter Rita Giordano that appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer, the region’s major newspaper. In addition to being posted here, the article was re-posted through Facebook and LinkedIn by WolfBrown, Carnegie Hall, and Dennie Wolf’s personal accounts, and appears on the WolfBrown website.

With the help of the Lullaby Project, moms are creating custom songs for their children

JOY, LOVE and AWE interweave the lyrics of lullabies as was evidenced at a recent concert sponsored by the Rowan School of Music’s Lullaby Project and reported on by The Inquirer on July 8, 2023. The project invites mothers and caregivers to create lullabies for their babies with the help of professional musicians and music educators. It is part of the Lullaby Project, an initiative of Carnegie Hall’s Weill Music Institute. Its focus is on family engagement, music in the early well-being of young families, and the role of parents as first music teachers.

At the center is the way that the chance to be musically creative can reward and sustain caregivers who are doing the vital and complex work of raising a next generation in today’s often challenging and unsettled world.

The project also improves bonding and understanding. Says Dr. Dennie Wolf who’s been studying the impact of the Philadelphia Lullaby Project as part of an NEA Research Lab, through the process, participants "come to see their children in much more complex ways."

In research which will be published soon, she’s found that caregivers involved in the project feel more empowered, have more satisfaction in their role as caregivers, and develop more understanding of their children’s feelings and behaviors.

Kudos to the participants and the artists who work with them!

Learn more about Carnegie Hall’s Lullaby Project here: https://www.carnegiehall.org/Education/Programs/Lullaby-Project

REACH Lab Blog Entry #6 - ELLIE BROWN, DENNIE PALMER WOLF & STEVEN HOLOCHWOST

ELLIE BROWN, DENNIE PALMER WOLF & STEVEN HOLOCHWOST

Executive Summary: REPORT ON PHASE I OF THE REACH LAB

With support from the Arts Endowment, we have established The Research on Education and the Arts in Early Childhood (REACH) Lab. Our multidisciplinary team includes investigators with expertise in clinical child psychology, developmental neurophysiology, and arts education. In collaboration with leading arts organizations such as Settlement Music School, Carnegie Hall, and Play on Philly, we have studied the impact of music on self-regulation for children at risk via poverty, neurophysiological mechanisms of impact, and behavioral interactions linked to these effects. We have developed a website, blog posts, a convening, scholarly products, and applied tools, and have engaged researchers, policymakers, and practitioners in considering how music and the arts can mitigate poverty risk and promote equity.

With our arts partners, we’ve initiated this study at three distinct stages of early childhood, and in three unique contexts- first, with infants and toddlers engaged with their caregivers in joint music activity in the context of Carnegie Hall’s Lullaby Project; second, with preschoolers enrolled in Settlement Music School’s Kaleidoscope Arts Enrichment Program- a music and arts intensive preschool; and third, with early elementary school students engaged in Play on Philly’s intensive orchestral music education program.

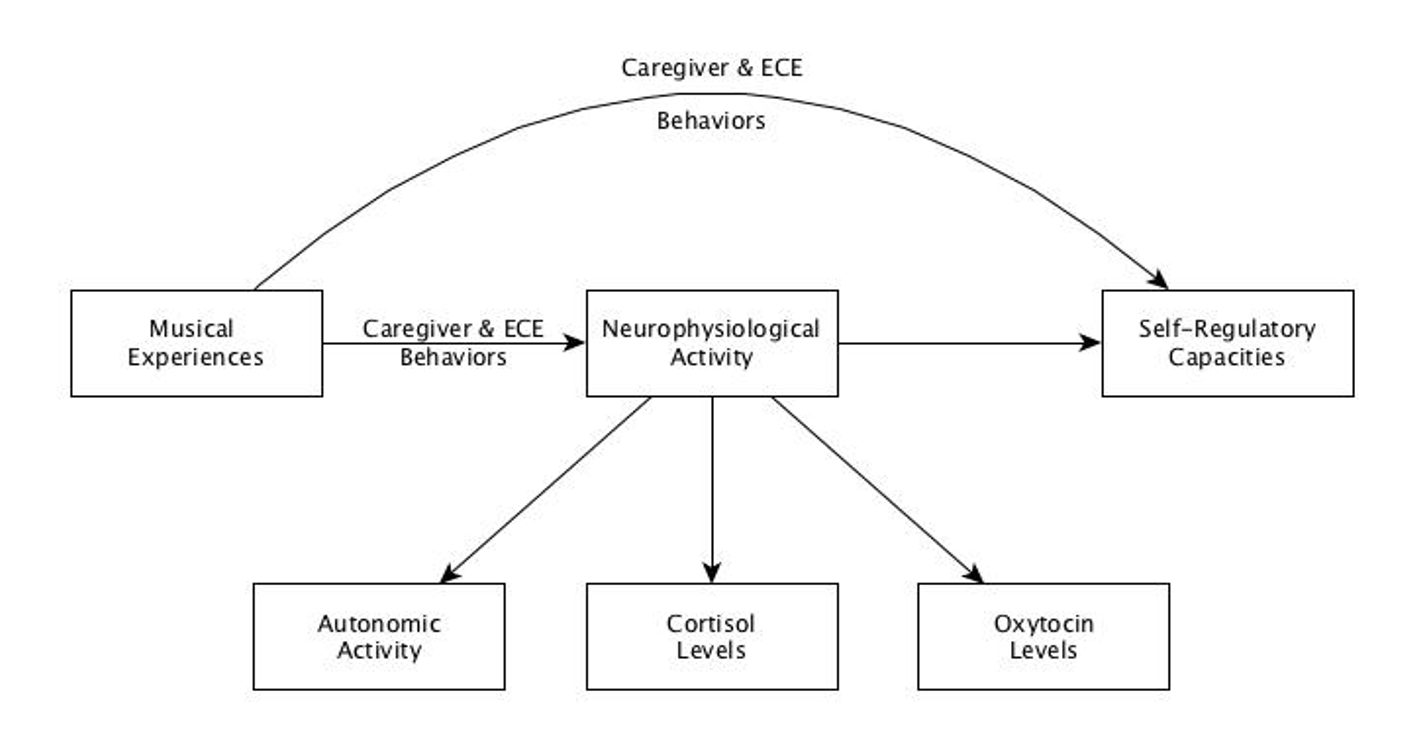

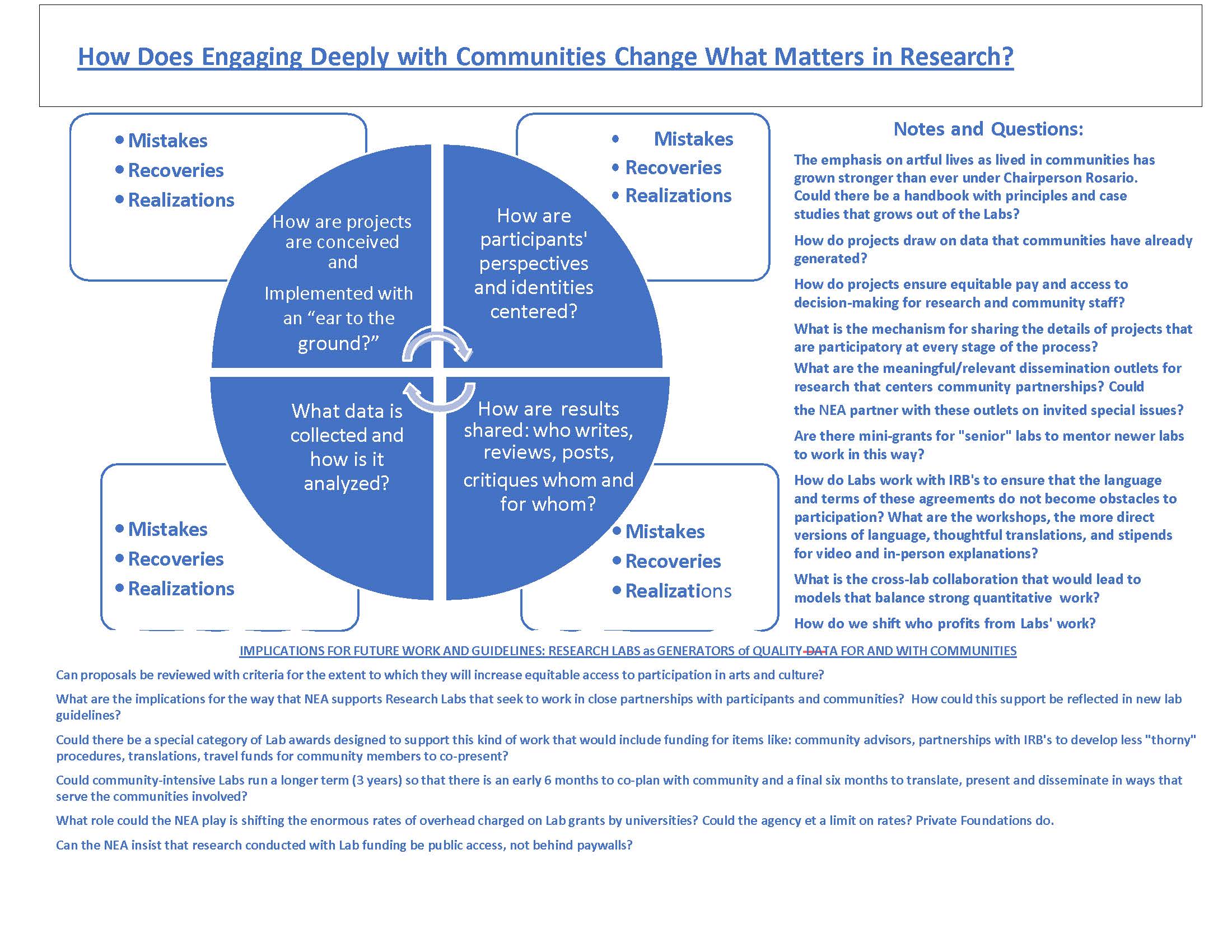

Figure 1. REACH Lab Model.

As illustrated by the model in Figure 1, for our initial research agenda, our REACH team has worked with children and families facing poverty risk, and with educators, to understand whether and how high-quality musical experiences can foster children’s self-regulatory capacity or the ability to modulate emotions, attention, and behavior in the service of learning and prosocial interaction. We have investigated whether music’s effects on self-regulation are transmitted or carried by changes in children’s neurophysiological function- including levels of the stress hormone cortisol, the prosocial hormone oxytocin, and autonomic nervous system activity, and we have begun to identify specific aspects of musical experiences, as defined by caregiver and early educator behaviors, that are especially important promoters of these changes in neurophysiological function and self-regulation.

We’ve focused on the following questions:

First, what are the social and/or emotional-related health benefits of participating in music?

Our longitudinal case study research on the impact of participating in Carnegie’s lullaby-writing project has indicated associated increases in caregivers’ role satisfaction and parental self-efficacy, both of which are well-established dimensions of wellbeing with demonstrated correlations to the quality of relationships in early childhood.

Our quasi experimental and longitudinal studies with Play on Philly have indicated that intensive orchestral music education can promote children’s persistence in the face of challenge.

And our experimental and quasi-experimental studies with Settlement’s Kaleidoscope Preschool Arts Enrichment Program have demonstrated that children’s participation in music, dance, and visual arts classes relates to reductions in levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

Second, what psychological mechanisms or group dynamics are at work in achieving those benefits or related outcomes?

One example is that, in Carnegie’s Lullaby Project, our research has suggested that by engaging in joint music activities with their child, caregivers exhibit growth in their mind-mindedness, or capacity to interpret and respond to their child’s behavior in light of the child’s internal states, emotions, and intentions, as well as increased mutuality in their interactions with their children.

Another example is that, at Settlement’s Kaleidoscope Preschool, we probed the role of early childhood music teachers and asked, “to facilitate the stress reduction benefits of music, should teachers guide or get out of the way?” Our results suggested that stress reduction was facilitated by high quality teacher-child interactions but also by children having the opportunity to direct music activities- some autonomy and control. That study recently was published in Mind, Brain, and Education.

Third, what kinds of activities are invoked in these relationships, and at what levels of participation?

At Settlement Music School’s Kaleidoscope Preschool, we’ve deconstructed the music and dance classes to examine which activities particularly are linked to stress reduction, and we’ve found that children’s active engagement in singing and creating movements is particularly powerful. A further study of visual arts classes at Settlement’s preschool has highlighted again the importance of teacher-child interaction, finding particular stress reduction and other emotional benefits of visual arts activities that involve high levels of teacher interaction.

Conclusion

We are guided by the idea that music and the arts cannot erase poverty, but that they may have the potential to counter some of the toxic effects of adversity on young children. With support from the Arts Endowment, our REACH team has been honored to collaborate with community music and arts organizations, in order to advance scientific understanding of how those experiences may promote health and wellbeing for young children and their families.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #7 - Ellie Brown Interviews Padmaja Charya (Part 1)

Ellie Brown Interviews Padmaja Charya (Part 1)

Interview with REACH Doctoral Student Padmaja Charya: Part 1

Our REACH team has been invigorated by training and collaborating with junior scholars, including WCU doctoral student Padmaja Charya, who was drawn to our lab in part based on her own connection to music and dance. Recently, I had the chance to learn more about her experiences through this interview, which provided me with insight into how Padmaja came to pursue a doctoral dissertation on dance and trauma.

When and how did you first become interested in dance?

If you were to ask my mother, she would tell you that I was enamored with music and dance from the time I was a toddler. On a daily basis, I was begging my parents to play MTV so that I could dance to Michael Jackson.

I remember becoming aware of my love for dance when I was a teenager in high school and began to explore different genres of music with my cousins. I come from a musical family, so I have fond memories of my father singing, dancing, and listening to music with me. He was probably the first person to introduce me to the arts simply by being his authentically musical self!

What kinds of dance did you participate in as a child?

As a child, I would dance in my living room to whatever music my parents and friends would play, which was mainly 80s and 90s American pop and hip hop, as well as Indian classical and pop music. In my childhood home, music was always playing from the speakers of our living room and basement, courtesy of my father. When I became a teenager, I would be the one playing the music! I would often sneak my portable CD player into my bedroom and create dance routines to the music spilling from my headphones.

I did not take my first formal dance class until I was a 19-year-old college student living in Philadelphia. My first formal dance class was a hip hop class at Koresh Dance Company. To this day, I take classes and attend performances there from time to time. As I have continued my exploration of dance, I have learned other genres of dance, including contemporary, Latin, African, flamenco and ballet.

In terms of music, prior to the hip hop class I took, I was regularly involved in classical music instruction, playing musical instruments, and performing in concert band and solo recitals, since around 9 years old.

Do you have an early memory of dancing that stands out to you?

I remember when Madonna’s Blonde Ambition tour was happening in the 90s--second to Michael Jackson was Madonna. I had been entranced by her performances on TV. Luckily, for me, my parents recorded her tour performance on a VHS tape!! I remember when one day, the video was playing in my living room, and I was exuberantly dancing around in a circle with my childhood friend. I just remember feeling so free and overcome with joy.

Also, I remember being so incredibly moved by the music of Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker. To my younger brother’s dread, I would pretend to be the artistic director for The Nutcracker ballet, where I would dress my brother and our childhood friend in costumes and arrange them in dancing positions on the “stage,” located in the basement of our babysitter’s house. My poor brother!

What would you say about the influence of dance on your childhood?

Dance gave me a form of expression that was automatic and natural. I was a shy, quiet child. I remember that I tended to observe and listen rather than to speak, which would sometimes be misinterpreted by children and adults. Dance was the messenger for my innermost core self, my soul, my spirit. Dance was a nonverbal way to communicate the sentiments and facets of my identity that words could not capture. Of course, I did not fully understand my relationship with dance until I was in my twenties.

I remember walking into my first dance class later in life and having a rush of euphoria and vindication hit me--I had discovered a way to communicate my identity, thoughts, and feelings without words. I was starting to understand the significance of movement and music in my life.

I know you're still involved with dance now- tell us what that looks like for you currently.

Lately, I’ve been participating in Latin dance, which consists of salsa, bachata, and cumbia. Years ago, my friends introduced me to the different styles of Latin dance, and my favorite style is salsa. From time to time, I take a virtual hip hop dance class through a dance school I discovered during the pandemic. I took a break from ballet, because the classes are held during times that conflict with school.

Some people stick with the activities they begin in childhood and others move on- why do you think dancing has remained part of your life?

What’s sort of profound is that I do not believe I ever effortfully pursued dance. It has always felt like dance just found me, grabbed me, and guided me into today. It is a blessing and a privilege to recognize this and to have been placed by my parents and other adults in spaces where I could be and still can be a part of the arts. Continuing my involvement with dance was the only option that made sense, because it is such a fundamental form of my self-expression. It is the way I communicate and make sense of my world.

You've mentioned that you have used dance to promote your own psychological wellbeing. What has that looked like at different times in your life?

Through dance, I have experienced healing from devastating losses and other painful life events that cannot be healed solely through verbal communication.

At the REACH Lab, we're particularly interested in how music, dance, and other art forms can be used to support children to cope with stress and trauma. Is that something you can relate to personally? If so, how?

The impact of stressful and traumatic events can be all consuming. When I dance, especially if the dance class is more structured and demanding like ballet, it requires such close attention to your mind and body that little room is left to remain stuck in the stressful experience. Due to its mindful nature, dance can place me in the here and now, rather than in the “should have” or “what if.” For these reasons, dance has carried me through devastating losses of family members and friends, and it has helped me cope with harsh life events. I often leave dance class feeling grounded, light, and at ease.

What do you hope to accomplish with your dissertation research focusing on music and dance for children who have experienced trauma? What do you hope might be implications for clinical practice?

I mentioned that there are limitations to processing trauma solely through verbal communication and instruction. Our survival instincts are primitive and basic, and the areas of the brain linked to traumatic stress can be accessed and impacted through music and movement. Human beings are also hardwired to respond favorably and communicate through music and movement. I am examining how music and dance programming impacts preschool children who have experienced trauma, as individuals with trauma have been found to have elevated levels of cortisol--the key stress hormone.

It is my expectation that through regular involvement in music and dance, children may experience a reduction in stress levels. If so, this would strengthen the argument that arts programs matter in early education, and that integrating music and dance into early childhood curriculums could enhance outcomes will be for children who have experienced trauma. On a broader level, each healed child will have a lasting healing impact on our larger systems- economically, academically, vocationally, and relationally. I believe we have a social responsibility to care for our most vulnerable people, such as children who have been psychologically wounded by traumatic events. Arts-based interventions are one way to do that.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #8 - Ellie Brown Interviews Padmaja Charya (Part 2)

Ellie Brown Interviews Padmaja Charya (Part 2)

Our REACH team has been invigorated by training and collaborating with junior scholars, including WCU doctoral student Padmaja Charya, who was drawn to our lab in part based on her own connection to music and dance.

Recently, I had the chance to learn more about this connection through this interview. Part 1, posted in a prior blog, focused on how Padmaja’s experiences led her to a dissertation project on dance and trauma. In Part 2, I learned more about Padmaja’s perspective on music and dance as mechanisms forfacilitating clinical psychology practice.

You're currently conducting a dissertation project with the REACH Lab examining how music and dance might promote stress regulation for children who have experienced trauma. How have your own experiences in your personal life or as a clinician shaped your interest in this area?

Having directly experienced the healing impact of movement, I approached my role as a mental health clinician with an open mind to integrating small arts-based activities into my therapy sessions. I did this especially with children, who often do not yet have the level of sophisticated verbal abilities to regulate their emotions solely through typical therapist-patient dialogues. I began to experiment with instruments and music, giving patients the option to choose their musical activity to communicate their feelings.

Some of my patients would be instantly drawn to the huge electronic keyboard in my office, and others would request that I play songs of their choice as they engaged in spontaneous or improvisational dance. I would record the music each child created in therapy and play the recording to them. They would seem so proud and fulfilled by the art they created. These arts-based experiences were powerful. Patients were free to just “be” through the music.

Once I let go of the need to adhere to a standard agenda in sessions, I noticed a shift within my clients as well as within myself. I began to focus on fostering spaces for people to take the lead through music.

Any recommendations for clinicians who might not be experienced with the arts themselves?

If you’re a clinician, I encourage you to try an arts class and pay attention to what comes up for you! Take a local dance class, which not only would expose you to something new and potentially enjoyable but also would support local artists.

The mind-body duality and the benefits of integrating movement into therapy is supported by research. Dance is somatic and promotes body and mind awareness, which is meditative. I hope that creative therapies will become appreciated enough to be seen as a standard part of clinicians’ training.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #9 - Highlights from the Music as Medicine Convening

Highlights from Music as Medicine Convening

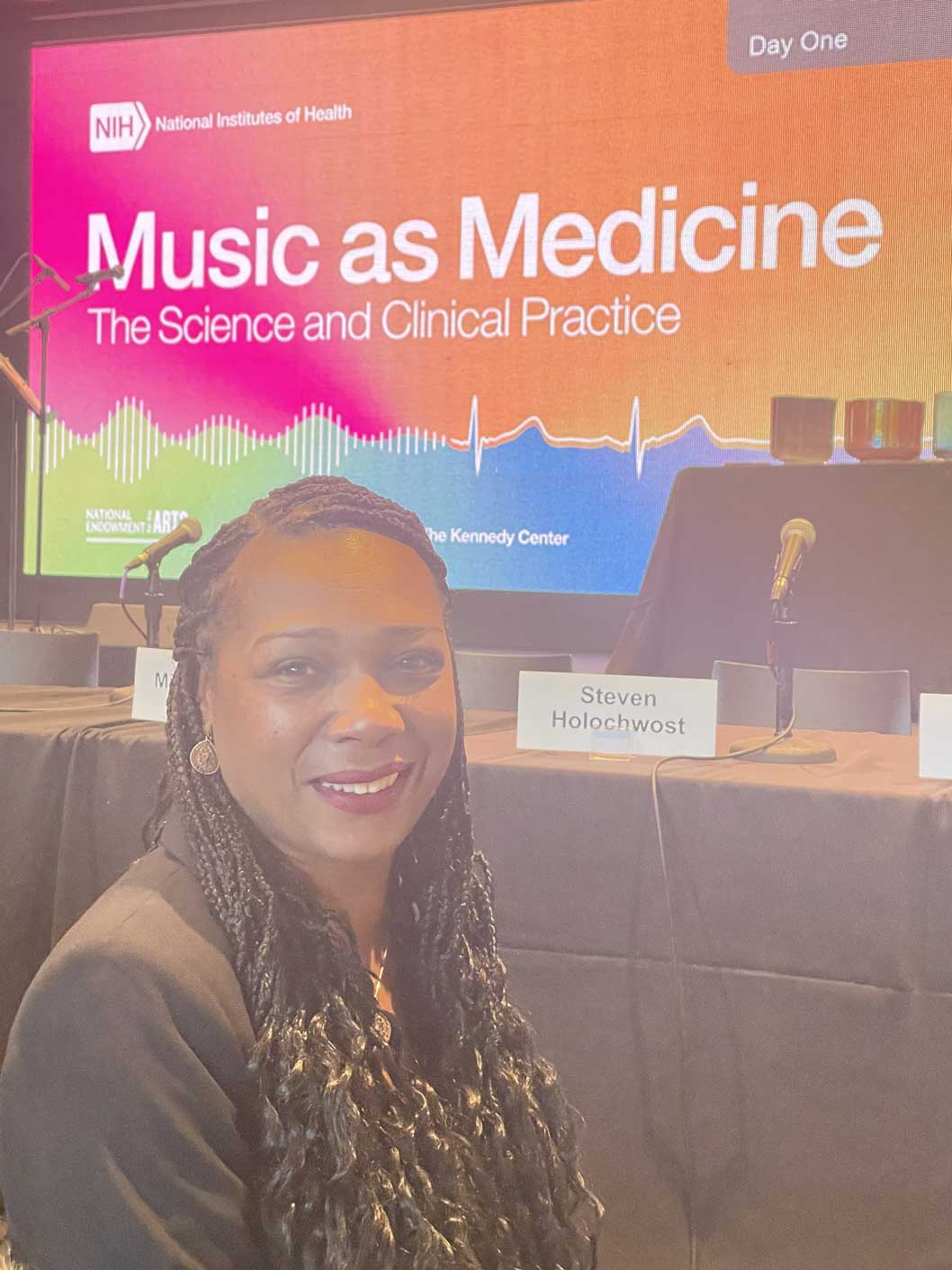

REACH Team members were excited to participate in the NCCIH Music as Medicine Workshop!

Tarrell: REACH partner Tarrell Davis, Settlement Music School’s Executive Director of Early Childhood is ready for Day 1 of the workshop to begin!

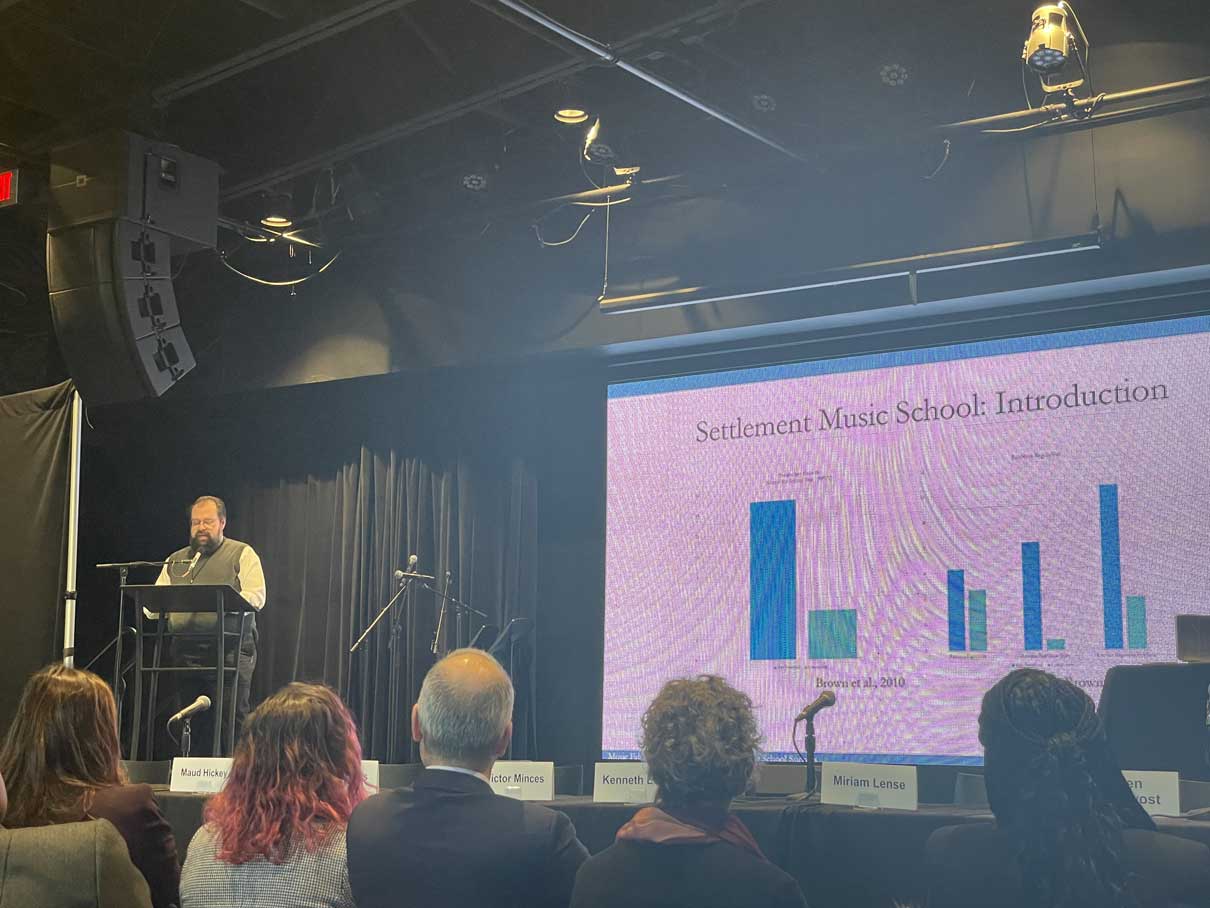

Sunil: Sunil Iyengar, NEA Director of Research and Analysis opens the session on Music Education and Health, which will feature REACH projects.

Steven: Steven Holochwost takes the lead in presenting highlights of REACH projects that he, Ellie Brown, and Dennie Palmer Wolf have conducted.

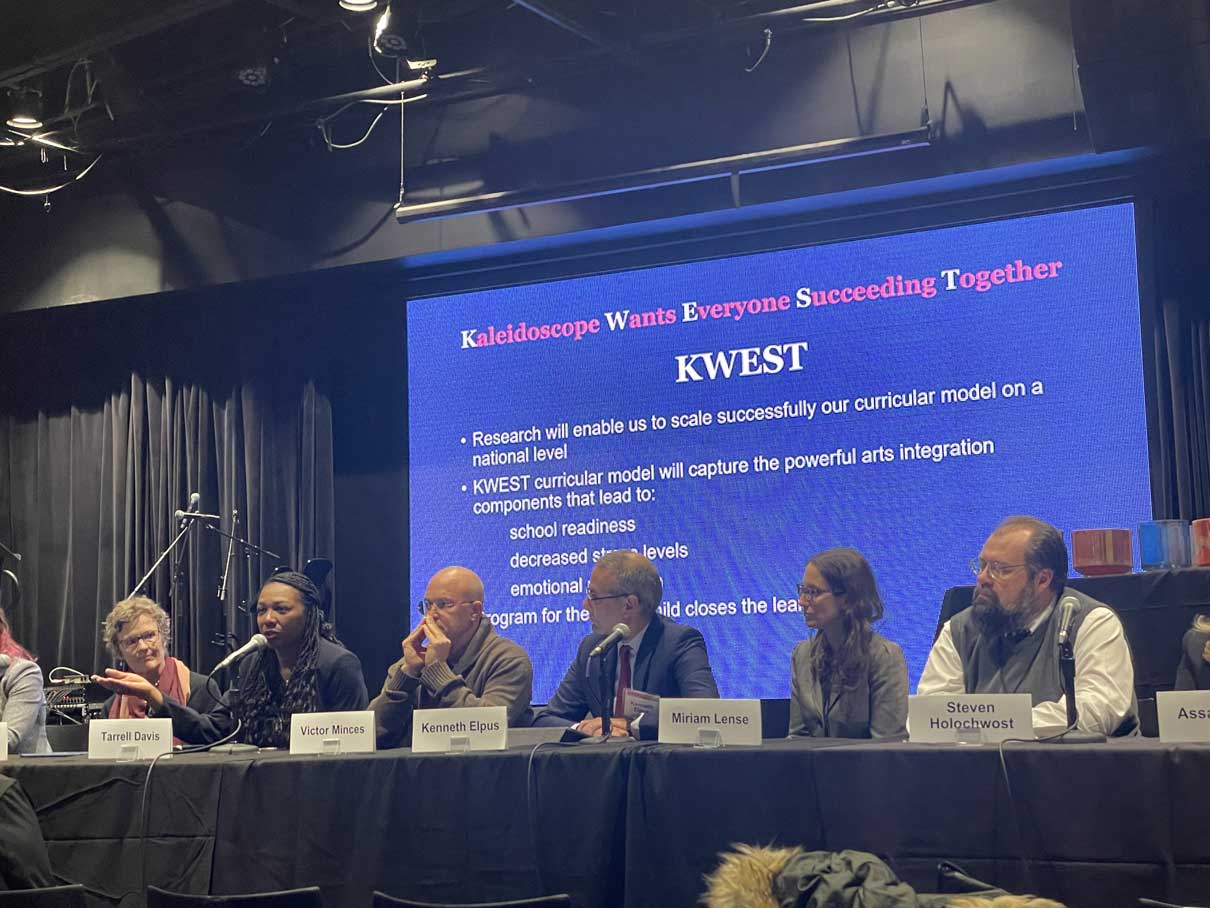

KWEST: Tarrell Davis shares about the community impact of REACH- explaining how the research is supporting development of KWEST- Settlement Music School’s scalable model for arts-integrated early childhood education.

REACH Team: Tarrell, Ellie, Dennie, and Steven were pleased not only to represent REACH at this federal interagency convening but also to learn more about cutting edge research on music and health taking place across the country.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #10 - Highlights from American Educational Research Association (AERA)

Highlights from American Educational Research Association (AERA)

REACH Team members were excited to present in a paper symposium at the American Educational Research Association (AERA) Conference in Philadelphia in April!

The session, chaired by NEA Program Analyst Melissa Menzer, was titled, "Arts Learning across the Lifespan: Social-Emotional, Cognitive, and Physiological Benefits."

Our paper was titled, "Creative Movement and Yoga Relate to Stress Reduction for Children in Head Start Preschool," and focused on preliminary results of the Creativity and Calm project supported by the NEA and described here.

Here is an abstract of the research we shared, which we're excited to develop further!

Introduction: The present study examined whether a creative movement and yoga program designed to for Head Start preschool might reduce cortisol levels for children facing stress related to poverty. Over the past 20 years, research has clarified the toxic effects of chronic stress and trauma (Blair & Raver, 2016). High levels of stress hormones that result from poverty and related adversity can flood brain areas involved in cognition and emotion, and harm physical health. During the same 20 years or more, creative arts programs have faced jeopardy, losing public funding and space in school curricula (Parsad & Spiegelman, 2012). Yet as creative arts programs have been cut, practitioners and policymakers have turned to the healing arts practice of mindfulness to address effects of toxic stress (Van Dam et al., 2018).

Although research to date suggests positive effects of yoga and mindfulness (Gould et al., 2016), there is little research to guide the implementation of these programs with young children facing stress and trauma related to poverty. Further, we may be overlooking the value of creative arts, and abandoning creative arts programs that could build on child and family strengths and contribute uniquely to combatting effects of stress and trauma (Brown et al., 2017).

Method: An experimental design facilitated testing the impact of experimental yoga and creative movement classes for children in a Head Start preschool. The Head Start randomly assigned children, by preschool class, to receive yoga, creative movement, both, or a control condition (with programming as usual). Children provided saliva samples just after yoga and creative movement or control classes and these samples were assayed to test levels of the stress hormone cortisol.

All children in the Head Start were eligible for participation, and approximately 70% participated. Parents or guardians provided informed consent. Children provided assent before saliva sampling via a cotton swab placed in their mouth for approximately 1 minute. Samples were analyzed for levels of the stress hormone cortisol using standard procedures.

Results and Discussion: Hierarchical Linear Models or HLMs, which were appropriate for the nested data, examined the impact of experimental yoga and creative movement versus control classes on stress levels. Children showed lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol following both yoga and creative movement in comparison to control classes.

This is the first experimental investigation we know of to document cortisol reductions correspondent to participation in yoga/mindfulness for children in Head Start preschool. The present results encourage a scalable model of arts and mindfulness for preschool children who face stress related to poverty and other forms of environmental adversity.

Authors:

Eleanor D. Brown

West Chester University

Steven Holochwost

CUNY Lehman College

KJ Mosley, Kate Anderson, Susan Gans, Zachary Weaver, Afolabi Shokunbi, Madeline Mazurek,

Estefania Ortiz, Benjamin Wolfe

West Chester University

REACH Lab Blog Entry #11 - Dennie Palmer Wolf Reports on NEA Labs Summit

Dennie Palmer Wolf Reports on NEA Labs Summit

NEA Research Labs Summit – June 3 – 4, 2024, Washington DC

In early June the National Endowment for the Arts brought together 18 members of its national network of Research Labs to share approaches and findings and to discuss the issues raised by their work. PI from the REACH Lab, Dennie Palmer Wolf, chaired a panel, "The Power of Proximity: The Enriching and Challenging Consequences of Community-engaged Work," that focused on the vital – and sometimes difficult -- ways in which community-engaged research raises questions about how we examine the impact of the arts on human lives. Wolf spoke to the early challenges faced by the Lullaby Project, a collaboration between REACH investigators, Carnegie Hall, and community childcare providers in Philadelphia. She shared how the partnership with trusted center directors, teachers, and caregivers informed and dramatically changed the design of the project, with the result that enrollment, persistence, and satisfaction rose for both participating families and the teaching artists who had joined the research team. Similarly, Wolf shared how engaging caregivers as co-researchers changed the depth and quality of project data. Based on these learnings. Collaborating REACH partner, Tarrell Davis, Executive Director of Early Childhood at Settlement Music School, corroborated the importance of this kind of "ear-to-the ground" knowledge in working with families. With the REACH team, she and Wolf are exploring potential synergies between the Lullaby Project and Settlement's Kaleidoscope Preschool which could make music a partner in early development 0 – 5.

Wolf was joined by representatives of three other labs, each of whom spoke to additional ways in which intimate and ongoing partnerships with participants and larger communities fundamentally shifted how they conducted their research:

- Nathaniel Stern, University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, ABLE (Autism Brilliance Lab for Entrepreneurship)

- Jane Prophet, University of Michigan, Commissioning Public Art through Community Engagements

- Emily Hartlerode, University of Oregon, Oregon Folklife Network, Traditional Arts Apprenticeship Program

Throughout the session, audience members used a specially-designed graphic to take notes on how they entered, explored, and wrote about the impact of the arts – and the issues they encountered. This interactive approach yielded a lively "gallery" of comments and questions.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #12 - Dennie Palmer Wolf Reports on Lullaby Convening

Dennie Palmer Wolf Reports on Lullaby Convening

Lullaby Convening: May 30 – June 1, 2024, Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall's Lullaby Project brings well-documented benefits of music-making to the urgent work of supporting the well-being of young families: both caregivers and children. It is also one of the collaborating partners in REACH's program of investigating and documenting the ways in which access to high-quality arts experiences can counteract stress related to poverty and other adversity. At the end of May, the growing international network of Lullaby Projects came together in New York to share project strategies and outcomes with one another. Half a day was devoted to exploring how the naturally-occurring materials of Lullaby Projects (e.g., lyrics, interviews, play sessions between caregivers and children) can be used to document and research the impact of such projects. REACH-affiliated researcher, Dennie Palmer Wolf, alongside early childhood educator, Linda Russell, shared original interviews and early findings on how mothers' self-efficacy and role satisfaction grow throughout the project. Additional Reach researchers, Kate Anderson and Anusha Mohan used project data on play interactions to explore how the mutuality of caregiver-child interactions, along with caregivers' reflectivity, increase across the sessions. Some of these early findings are shared in the recently published volume from Oxford University Press, edited by Rosie Perkins, Music and Parental Mental Well-being.

REACH Lab Blog Entry #13 - Dennie Palmer Wolf Reports on Lullaby Presentation to Harvard Medical School

Dennie Palmer Wolf from the REACH Lab recently joined Sarah Johnson and Tiffany Ortiz from Carnegie Hall for a presentation to the Early Child Development Working Group at the Harvard Medical School to discuss The Lullaby Project as a highly flexible public health intervention in child and maternal health initiatives globally. The group brings together health professionals from around the world who are working on improving the health and well-being outcomes for young children around the world.

In a short presentation, Johnson outlined the origins of the project as a support for New York mothers raising young children in challenging circumstances like shelters, half-way houses, and unstable family situations. Ortiz explained how, over ten years, the project has spread nationally and globally, as a low-cost, high-impact intervention that builds caregivers’ confidence and self-worth, as well as communication between them and their children. Wolf shared some of the initial data from free play sessions that demonstrates these consequences.

Group participants, many of them working in rural and under-resourced communities around the world, were interested by the low-tech, highly portable, and contextually adaptable nature of the Lullaby Project. They imagined making it a part of maternal-child health initiatives currently underway in the regions where they work. They also were attracted by the asset-based and potentially-joyous nature of the intervention. They saw the possibility of making creativity and exchange an integral part of early health care visits as a way of building trust and potential longevity into the system.